Mariano Fortuny Back in the Spotlight in New York

Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo, Cotton printed textile, 20th century; Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo, Peplos, 1910− 1920

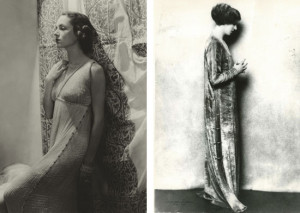

From left: Mrs. William Wetmore modeling a Delphos gown in front of Fortuny fabric. Originally published in Vogue, December 15, 1935; Countess Elsie Lee Gozzi wearing an Eleanora dress, 1920s.

Mariano Fortuny holds a special place in my heart which is why when I found out that the Queen Sofia Spanish Institute (QSSI) in New York will host an exhibition, “Fortuny y Madrazo: An Artistic Legacy” (November 30, 2012-March 30, 2013), I couldn’t wait for it to open. I became familiar the work of Fortuny in graduate school, particularly in my History of Textiles class when I was assigned to research a silk gauze tunic (c. 1925) in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. During my research I had the fortune of meeting Mickey Riad, whose family purchased the Fortuny name in the 1990’s and produces Fortuny fabrics to this day. Riad was generous with his time and gave me a tour of the New York City showroom (whose walls, like those in the Queen Reina Sofia galleries, are covered in Fortuny fabrics) and told me all about the designer’s history and influences. However, anyone who visits the incredibly in-depth exhibition at the QSSI will leave knowing as much about Fortuny as I did after a semester of research.

Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo (1871-1949) came to Venice with his family in1889. This was fifteen years after Mariano’s father, Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1838-1874), died in Rome at the age of thirty-six. Fortuny y Marsal was a talented painter and died at the height of his career when Mariano was only three years old. However he remained an important presence in Mariano’s life through his legacy and the collections which he amassed during his lifetime. Venice was chosen as a new home for the family, out of convenience and also because Fortuny y Marsal had always wanted to come and live here; this would be a tribute to him. The young Fortuny, who like his father was an artist, became enamored with Venice; its timelessness encouraged him to proceed with his interests of studying the history of art as opposed to succumbing to new trends and cycles. The start of Fortuny’s most creative period coincided with his move to the Palazzo Pesaro Orfei in 1899. The Palazzo Orfei eventually became the Palazzo Fortuny. On the walls hung textiles, alongside those inherited from his father: vast lengths of velvet that covered the walls and divided the great room like enormous curtains. The exhibition is very careful to trace the younger Fortuny’s influences and explores the work of Fortuny senior through a series of paintings and etchings.

Fortuny’s work in theater led him to experiment with textiles in 1906. His earliest clothing design was a “large rectangular veil to be worn by a dancer onstage, which adorned the body without dressing it. The idea behind this creation was to liberate a woman by allowing her to move as freely as a ‘dancer in flight.’” This design became known as the “Knossos” scarf and although at first worn on its own, it was later meant to be worn over a dress, the Delphos which appeared in 1907. Scarves were a logical first beginning for Fortuny. Initially, they served a purpose of embellishment. They easily adapted themselves to every kind of shape and provided Fortuny with new ideas. He turned these scarves into jackets, tunics, or wraps of silks. As Fortuny became more confident with textiles he started to experiment with other fabrics, such as velvets. The exhibition features an array of dresses, caftans, coats, scarves in the most beautiful colors: apricot rose pink, sage green, lavender, aquamarine, and champagne. Fortuny’s was not interested in fashion trends (although like his contemporaries he was in favor of the uncorseted body) and his designs practically never changed but that did not stop some of the most discerning tastemakers of the 20th century from wearing his creation. Marchesa Casati, Peggy Guggenheim, Eleonora Duse, Isadora Duncan (including her adopted daughters Lisa, Anna, and Margot, whose haunting photograph hangs in one of the galleries) were all fans. But perhaps no one wore the artist’s (I don’t think we can really call him a fashion designer) creations like his French wife, Henrietta. A photograph of her wearing a Delphos gown on the streets of Florence, which was very scandalous for the period because these loose fitting gowns sans corset were only meant to be worn in the privacy of your own home, shows that she was no doubt his muse. Several of Henrietta’s gowns are in the exhibition.

The exhibition also focuses on the exotic cultures that inspired Fortuny. Most of the prints on Fortuny’s textiles were drawn from 17th and 18th century Persian botanic motifs, Coptic art, traditional Moorish tiles and mosaics, and the Italian Renaissance. One thing that the exhibition doesn’t discuss in great detail is Fortuny’s secretive productive methods or the exact technique that he used for pleating the Delphos which to this day is also a mystery. The Delphos name comes from the bronze statue, The Charioteer of Delphos (475-70 B.C.) Fortuny’s goal was to recreate the chiton, a garment favored by Greek sculptors, found on the statute. He was interested in fabrication and the way it was draped around the body. Fortuny patented a technique for manipulating lightweight silk satin, unlike the wool or linen used by the Greeks, into silk pleats in 1909.

The unstructured silhouette of the Delphos, held together at the sides with Venetian glass beads, will forever remain an icon of 20th century fashion and is highly collectible today. Just last week I saw a beautiful raspberry colored Delphos in Maria Niforos’ shop at the Showplace Antique Center on West 25th Street in New York. I was too scared to ask the price knowing that one can cost in the range of $10,000. A major lender to the exhibition is a boutique called Vintage Luxury which has about twenty Delphos dresses for sale on its 1stdibs.com page.

The Queen Sofia Spanish Institute, whose chairman is Oscar De La Renta, is quickly becoming an important venue for fashion exhibitions in New York. Last year the mounted a fabulous Balenciaga exhibition and the year before a study of regional Spanish dress as seen in the paintings of Joaquín Sorolla. One can only hope that next year will be just as exciting.

The exhibition at the QSSI closes on March 30th. For more information visit the QSSI website.

2 comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

Archives

- June 2018

- March 2018

- December 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- June 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

Categories

- 20th c. design

- Architecture

- Art Deco

- Art Jewelry Forum

- Art Nouveau

- Auction

- Bard Graduate Center

- Blog update

- Brooklyn Metal Works

- Brooklyn Museum

- Ceramics

- Christie's

- Contemporary Art

- Contemporary Design

- Cooper-Hewitt

- Costume Institute

- Decorative Arts Calendar

- Design Exhibition Review

- Designer Spotlight

- Exhibition review

- Extraordinary lives

- Fashion

- Fashion exhibition review

- Fashion photography

- Film

- Fresh Talent

- Furniture

- Gallery Spotlight

- Glass

- ICP NY

- Italian Design

- Jewelry

- Lecture

- MCNY

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- MoMA

- Museum at F.I.T

- Museum of Arts and Design

- Neue Galerie NY

- On the Market

- Paper Art

- Paris

- Phillips de Pury & Company

- Pinakothek de Moderne

- Platforma

- Public Art

- Rago

- Recently Published Articles

- Russian Decorative Arts

- R|R Gallery

- Sculpture

- Sotheby's

- Television

- Textiles

- Travel

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Events

- Vintage Clothing

- Wiener Werkstatte

- Wright

Hi Bella, loved reading about this artist. Feels like he was one of the enlighted people that liberated women from the corsets. Hurray 🙂

He must have been a great influence on the charleston movement.

Theatres really did seem to be a place where people could push the boundaries of normal behaviour, clothing, art etc. Especially for women! Fortuny was in the right place at the right time to experiment with textiles and shapes. Bless his heart for liberating women so beautifully…. his gowns still look sensational 100 years later.